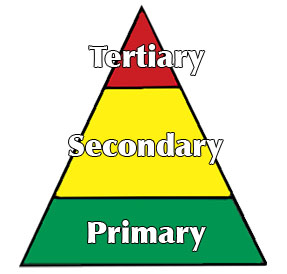

PBIS tiers addressed by this intervention approach:Tiers 2 and 3

PBIS tiers addressed by this intervention approach:Tiers 2 and 3

Many of the day-to-day behaviors that we perform, without even attending to what we're doing, are really quite complex, comprised of many smaller, discrete, singular, specific sub-behaviors that we perform in a certain order. Consider "one" behavior done easily even when you are tired and distracted: Brushing your teeth. When you think about it (which we rarely do), brushing is really a bunch of distinct simple behaviors performed one after another. Just analyze the task (Ah ha! Now you know where the name came from).

Brushing Teeth

Pick up the tooth brush

Wet the brush

Take the cap off the tube

Put paste on the brush

Brush the outside of the bottom row of teeth

Brush the outside of the top row of teeth

Brush the biting surface of the top row of teeth

Brush the biting surface of the bottom row of teeth

Try to make yourself understood while answering the question

of someone outside the door

Brush the inside surface of the bottom row of teeth

Brush the inside surface of the top row of teeth

Spit

Rinse the brush

Replace the brush in the holder

Grasp cup

Fill cup with water

Rinse teeth with water

Spit

Replace cup in holder

Wipe mouth on sleeve

Screw cap back on tube

Place tube back in room mate's toiletry/shave kit so s/he doesn't realize

that you forgot to bring toothpaste on the trip

While you may brush your teeth in a different order (and perhaps leave out the sleeve part), you get the idea. Others of you are already thinking: "Gee, each of those steps could have been 'broken down' or sub-divided into even smaller steps". For example, the first step, "picking up the toothbrush" requires the behaviors of locating the toothbrush, reaching toward it, grasping it, turning the bristles upward, etc. How small you decide to make the steps will depend on your best guess as to how well the student will be able to remember, understand, and perform the T.A. process and the sequential steps. Some individuals will display the desired behavior after only 5 steps being provided for them to follow. Others would need 20 increments in order to become competent in that action.

Task analysis is used most often with those who have problems mastering complex behaviors (e.g., individuals with autism, people who are mentally retarded or mentally ill, young children). Many of you have engaged in the process when non-impaired friends have asked "How did you do that?", all without even being aware it had been given a name.

More Examples Of Task Analysis (click on the one you wish to view)

Tying shoes (long and short versions)

Toilet training of a child with autism

Getting ready for home economics lab

Getting ready for math class

Making the perfect martini

| 7 minute Task Analysis video created by a former student of Dr. Mac |

The process of breaking a complex behavior (a chain of simple behaviors that follow one another in order) down into it's component parts takes a little practice, but soon you'll be able to construct behavior chains for the easier to analyze motor skills, followed by the more difficult to delineate academic and social behaviors. How are the "links" in the chain of behaviors developed? What process do teachers go through in devising the list of sequential actions? There are a number of ways: You might just imagine the desired behavior and write down the possible "steps". Or you might engage in that behavior, noting the sub-behaviors that lead to the final product. You could brainstorm with another teacher or aide, or consult with a more experienced colleagues who has probably taught the behavior before. Or, you can find one of the many texts that have task analyzed lots of common behaviors.

Once you have determined the sequence of the discrete links in the chain of a complex behavior, it's time to instruct the student in joining them together. As you might suspect from the lead-in of the previous sentence, the process of teaching the links in the chain is called "Chaining". The act of chaining can be accomplished in one of three ways. You might teach the behaviors from the beginning of the chain, requiring the student to display increasing amounts of simple behaviors at the front of the chain. As often as the student is able, s/he adds a new simple behaviors onto the tail end of the behaviors already mastered. As the learner links more and more of the chain, you have to complete fewer of the steps at the end of that chain of behaviors. Learning the behaviors from the front end is called "forward chaining".

You might decide (for reasons to be explained later) that YOU will perform all of the chain of simple behaviors...EXCEPT for the last one, which the student performs. Then you'll do all of the steps for him/her except for the last two behaviors. Then all except the final three, and so on. I'll bet that you can guess the name for this procedure...click here to see the answer

The third way that you might decide to teach the links in the behavior chain is through the process of "total chaining" in which the student performs all of the behaviors in the chain during every attempt (with your assistance and prompting given as needed). The steps for completing a long division problem would be taught in this manner. You guide the student though the process, helping a needed. The student performs every step in the process from the very first attempt at it.

| Click here to read a real life example/description of how a teacher used task analysis to teach a preschooler how to put on an over coat |

| Click here to read how a one-to-one aide used task analysis & praise to help a multiply handicapped 8th grader focus on her academic tasks and complete assignments. |

Activities

1. Select one or more of the following behaviors and task analyze them. Click on each one to see one possible listing of "links".

a. A youngster has a single parent/guardian with severe medical concerns. The youngster might have to summon medical help. Teach the youngster to "Dail 911 and summon help". Imagine that the youngster is either of preschool age, or is an immigrant youngster from a part of a country that did not have phones. Assume that the youngster recognizes the numbers 0-9 and knows that phones are used to talk to someone far away.

b. Task analyze "Finding a desired book in the library and checking it out".

c. Many students don't complete homework assignments because they don't know how or where to begin. For them, organization is an obstacle. Devise a list of behaviors for them to follow that will be pasted in the front of their homework book, They will (hopefully) follow the sequence of behaviors and submit the assignments the next day.

d. When your students enter your classroom in the morning, they don't seem to know what to do with coats, bags, etc. Task analyze "Getting ready for school"

2. Consider why you might choose to use a particular type of "chaining" (i.e., forward, backward, or total). What might be the benefits of each? Click here for some thoughts on this question.

Resources

To read case studies on teaching daily living skills through task analysis, log onto http://www.feat.org

Type "daily living skills" into their search engine.

To purchase software that will allow you to create "flow charts" and listings of steps, go to http://www.taskarchitect.com

![]()

| Fetch Dr. Mac's Home Page First, hold your mouse. Next, move it around on the rubber pad until the cursor is located inside the pink box. Then extend your pointer finger. Now press down on the left button on the mouse. |

Author: Tom McIntyre at www.BehaviorAdvisor.com

Author: Tom McIntyre at www.BehaviorAdvisor.com